The Sabarimala temple in the Pathanamthitta District of Kerala has long been revered as a sacred location and has been drawing increasing numbers of pilgrims in recent years. The temple is dedicated to Lord Ayyappa, a deity closely associated with forest lore. Riding a handsome tiger, the youthful Ayyappa is revered as a protector of the forest. What could be more appropriate for a shrine located in one of India’s 27 Project Tiger Reserves? The temple is situated in dense evergreen and moist-deciduous forests in the south-western corner of the 777 square km Periyar Tiger Reserve (PTR). For generations of devotees a pilgrimage to the Sabarimala temple is a sacred journey into the heart of an untarnished area. Human wants are forsaken and pilgrims are treated equally irrespective of caste or creed. In days past the temple was indeed very isolated and such a pilgrimage was no minor undertaking. Today much has changed as new roads and increased communication have allowed weekend if not day pilgrims to visit the forest temple with little inconvenience. The temple has become immensely popular in South India and the numbers of pilgrims during the short three-month season is estimated to be about 5 million (50 lakh) people!

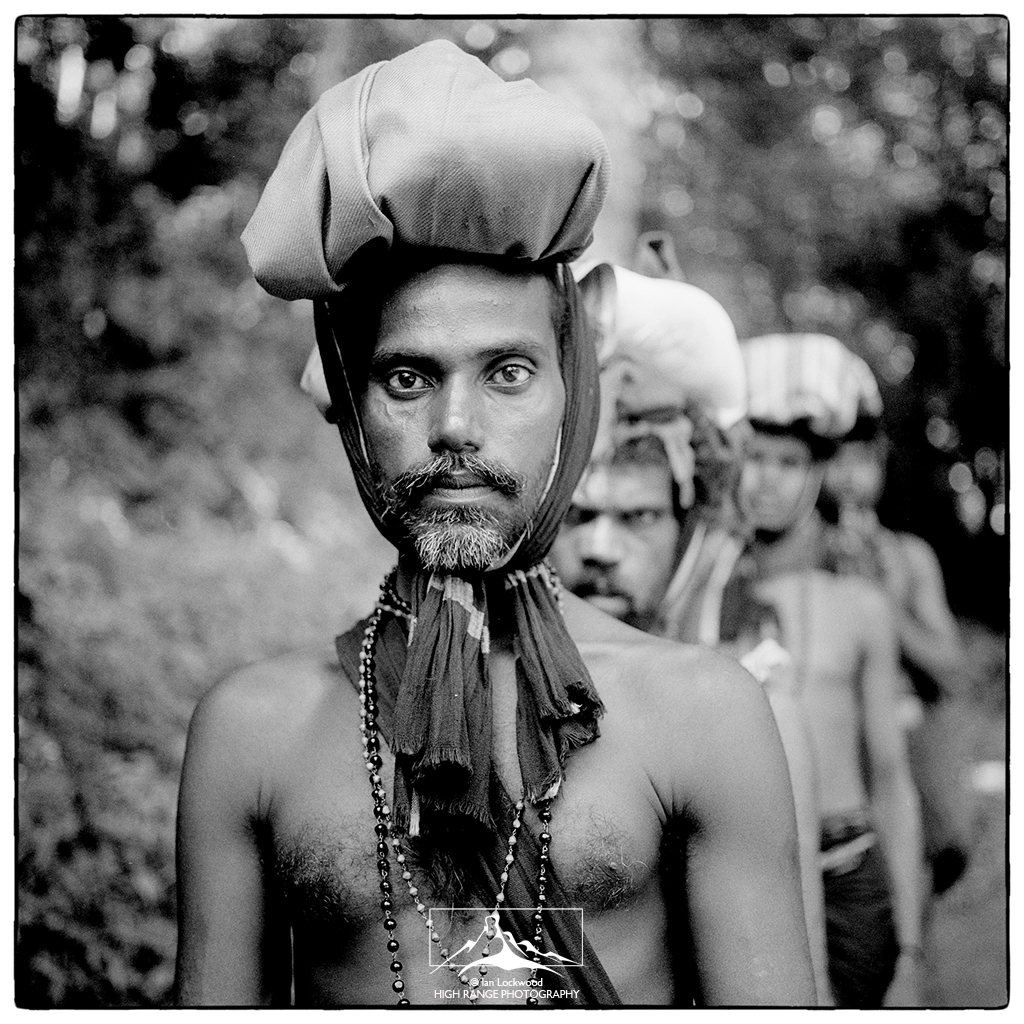

Sabarimala lies in the heart of some of the most expansive rainforests in the Western Ghats and it was for this reason that I set out to walk the path of an Ayyappa pilgrim. For many years I had watched barefooted pilgrims walking the hot roads of the south Indian plains on their way to Sabarimala. Clad in black lungis and outfitted with little more than a simple bag each, they traveled in small groups led by a guru. I was interested in observing the fusion of culture and natural history in the Western Ghats and good fortune finally lead me down the Sabarimala trail. I went with cameras and notebook and was not strictly-speaking a pilgrim. Rather, a curious observer, intent on discovering and recording the natural history, personalities and emotions of the pilgrim’s path.

Surely the biggest challenge posed by the Sabarimala shrine is the tricky balance of preserving cultural heritage and pilgrimage traditions within a fragile natural habitat and sensitive ecological zone in one of India’s two biodiversity hotspots. The job is not an easy one for the Kerala Wildlife Department officers assigned to protect Periyar. However, in the last decade several innovative ideas have emerged from Periyar Tiger Reserve and these have been acknowledged as a remarkable conservation success case (see Ashish Kothari and Sujatha Padmanabhan’s “Vision From Periyar”). The achievement of involving local communities in participatory conservation measures through ‘ecodevelopment’ is now well documented in the ‘Thekkady model.’ The efforts to manage pilgrim flow through the forest to Sabarimala were of particular interest to me as I set out on my walk from Thekkady.

To The Sanctuary

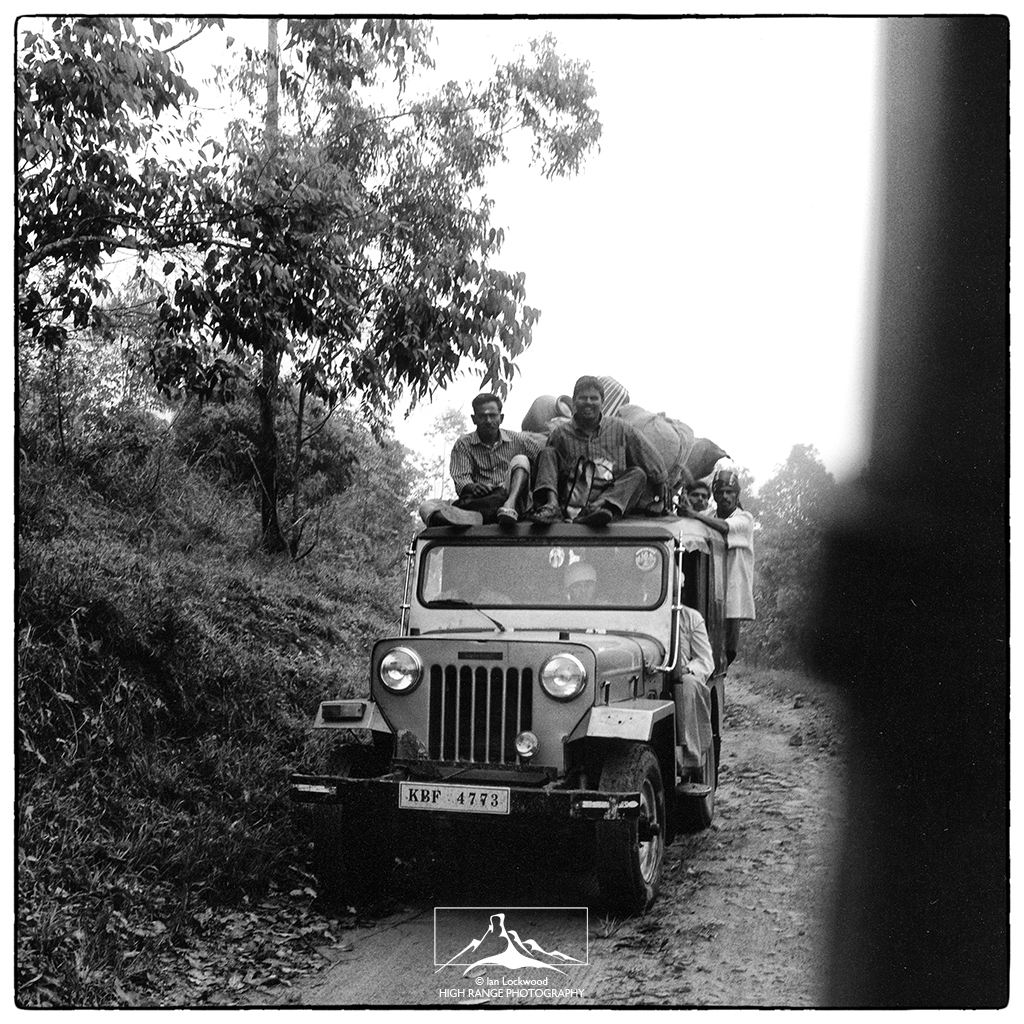

My journey to Sabarimala started in the early hours of a winter morning at the Kumily bus station near the headquarters of Periyar Tiger Reserve. My initial destination was Uppupara, the elevated roadhead approaching Sabarimala from the east via Vundiperiyar. It was still dark when I boarded one of the tomato red state transport buses that services Uppupara during the pilgrimage season. It was moderately full with shopkeepers and several pilgrim groups. The bus crossed over the Periyar River and then headed into the heart of the Tiger Reserve’s western borders. Here there are expansive grasslands intermixed with neglected eucalyptus plantations and patches of evergreen rainforest. Uppupara is little more than a line of shacks along with a forest check post, set amongst stunning grasslands landscape. It was bustling with activity as shopkeepers geared up for the groups of pilgrims going or returning from the Sabarimala temple, about a half a day’s trek away.

I stayed overnight at Uppupara, since I wanted to enjoy a full day’s time to descend slowly to Sabarimala. I was interested to meet and photograph groups of pilgrims and the unique grasslands landscape. I was also on the look out for the rare Broad Tailed Grassbird (Schoenicola platyura), an endemic Western Ghats species that is found in such mid-altitudinal grasslands. In the end I had more luck with the pilgrims than the Grassbird and was also rewarded with the sighting of a very shy Sambar stag on an adjoining hill. At night the temperatures fell and I was happy to have shelter at the forest department check post.

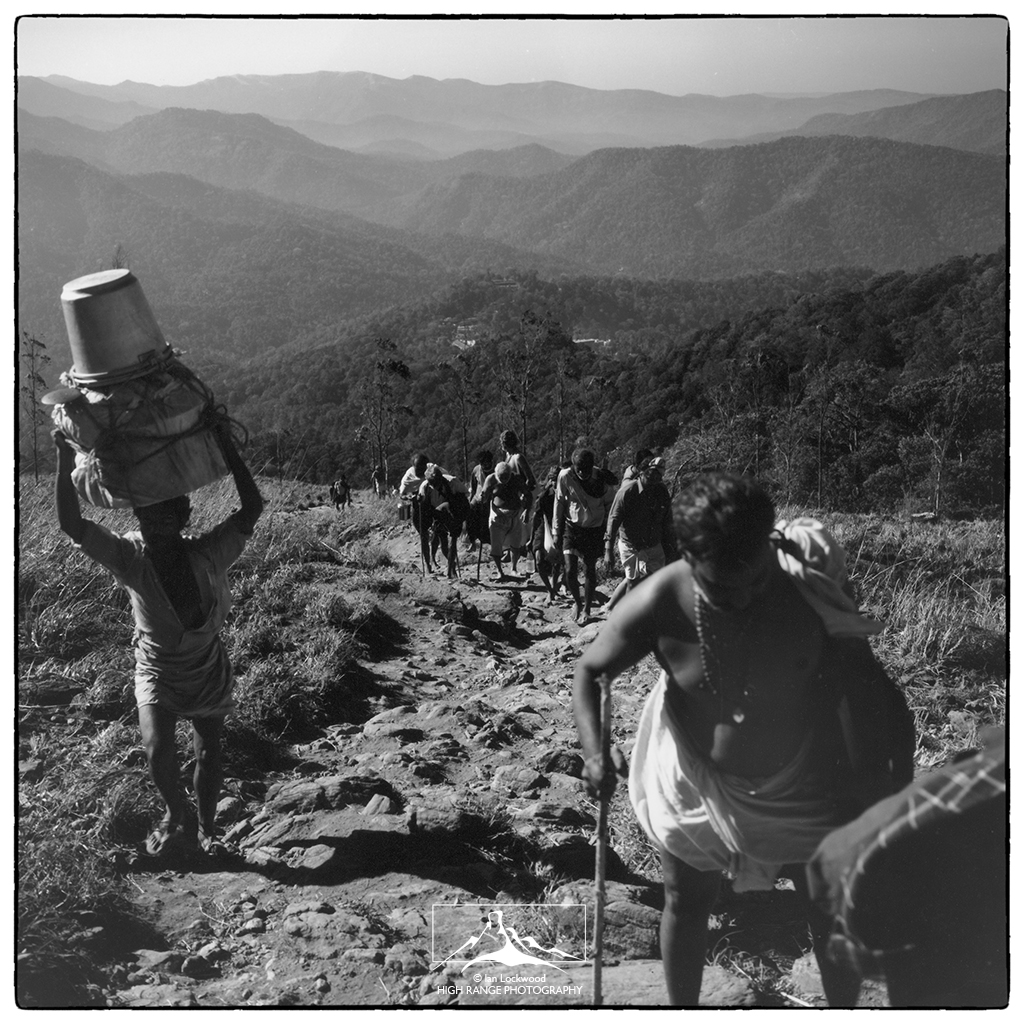

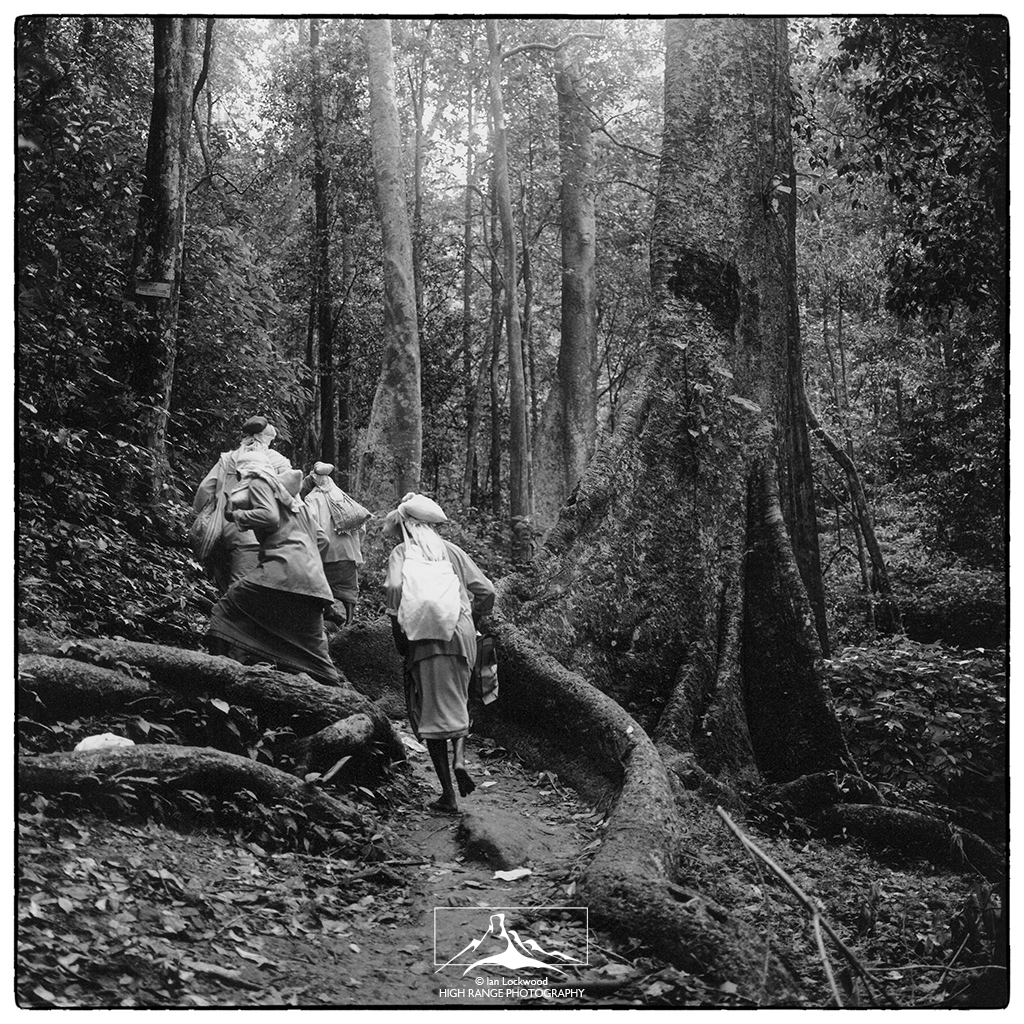

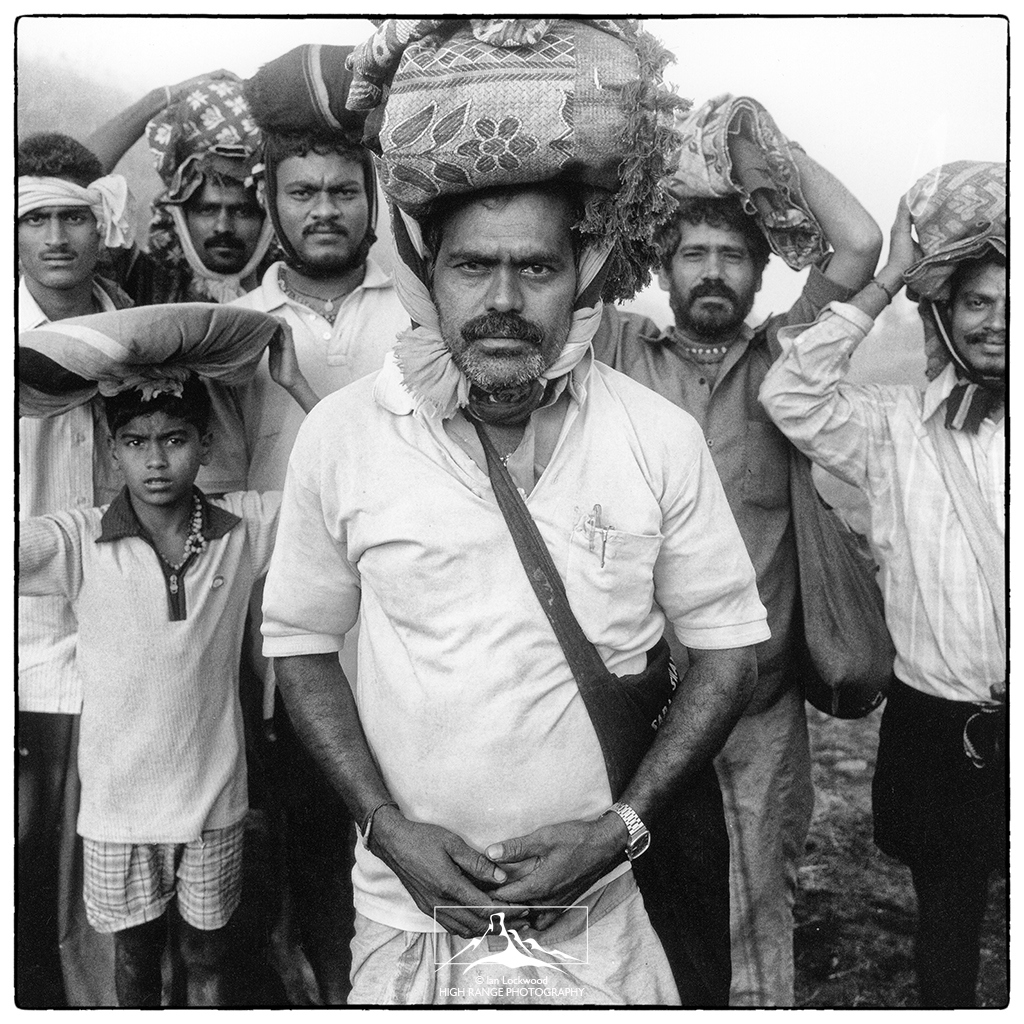

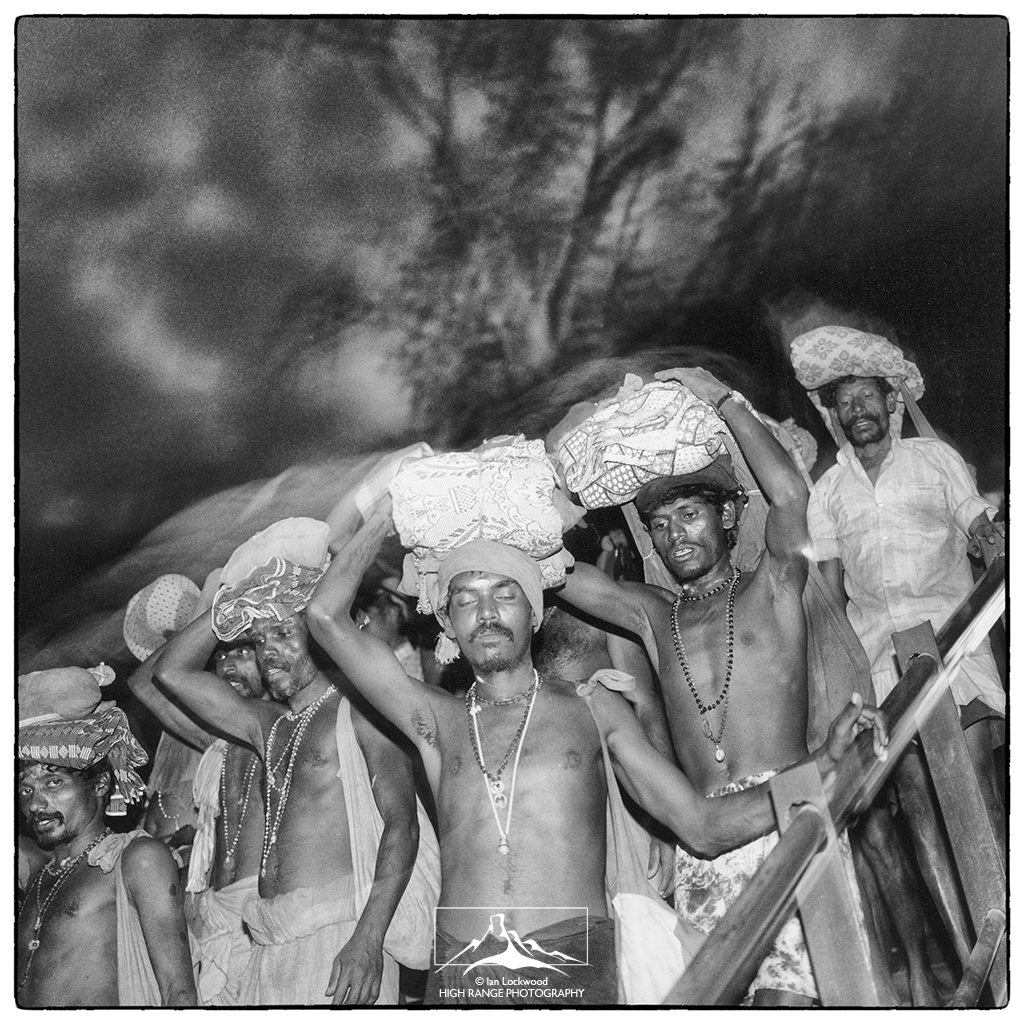

The next morning I walked leisurely down to the Sabarimala temple, though grasslands and then dense forests of mixed evergreen and moist deciduous vegetation. The morning was gloriously clear. At the edge of the upper plateau I had a commanding view of the temple and the adjoining valleys of forest. Numerous groups were making their way down the path and soon we were met by a steady stream of pilgrims on their way up to Uppupara. The pilgrims going towards the temple carried the conspicuous erumlei offerings above their heads. Chants of “Swami Ayyappa” mixed in with the mournful call of a pair of Crested Serpent Eagles (Spilornis cheela) circling above. The path entered the forest edge abruptly and I was happy to have the shade on this very bright day. Terminalia sp. and other large trees cast deep shadows over the broad pilgrim’s path. Bright colored scarlet minivets (Pericrocotus flammeus) flittered in the high canopy, oblivious to the many humans moving like large ants on the path.

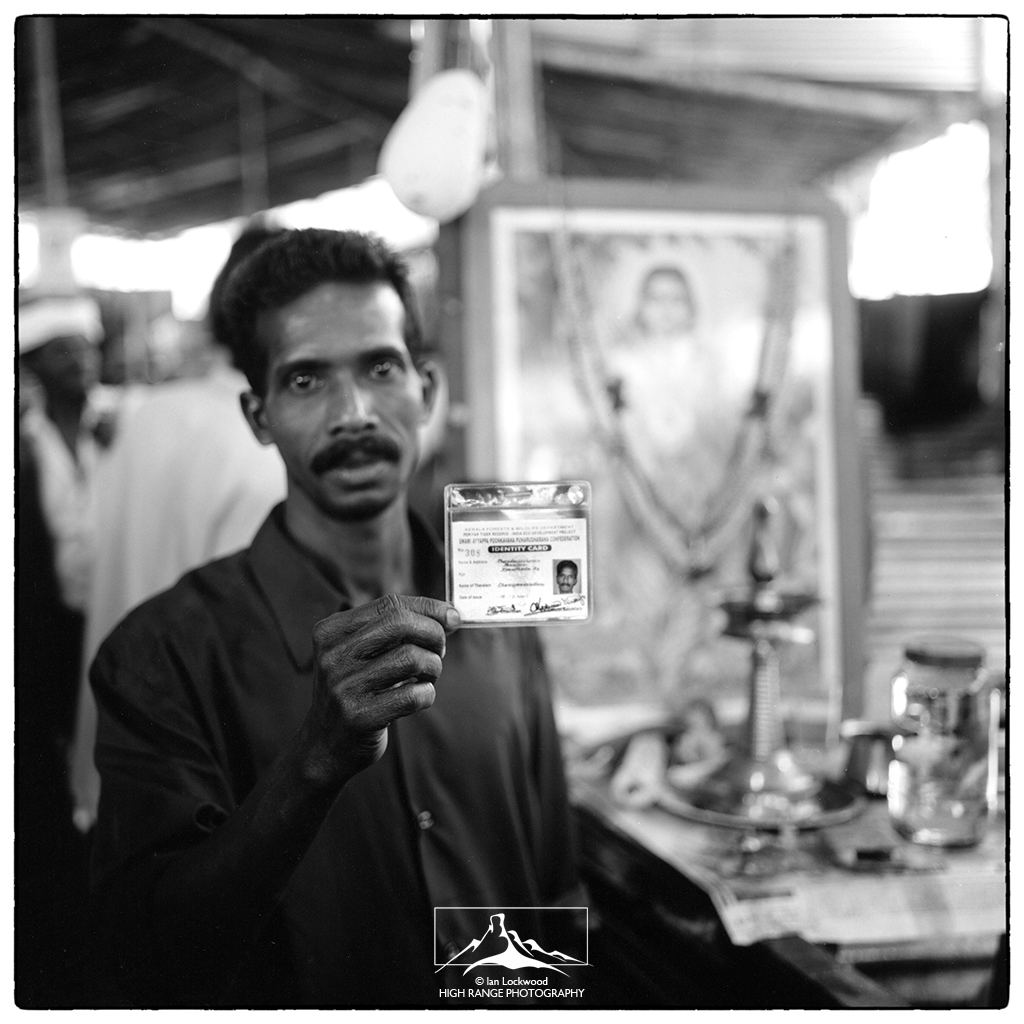

Sprinkled along the path are a string of shops for pilgrims facilitated by the Kerala Forest Department and run by “eco-development committees” (EDCs). This involvement of local communities as stakeholders in conservation has been one of the most successful aspects of the Thekkady Model. EDCs have been involved in activities such as guided nature walks near the visitor center at Periyar Lake. Reformed poachers and arrack brewers have been incorporated into EDCs to lead adventurous treks to the heart of the reserve. In all of these models the EDCs have directly benefited from conservation based tourism. A dividend has been the far decreased incidences of poaching and illegal wood-cutting.

Historically the shops on the Sabarimala path were tightly controlled by the temple authorities (Travancore Devaswom Board). Shopkeepers had to pay large fees to run their operations and making a meager profit was difficult. This often meant illegally cutting firewood from the forest or neglecting their large quantities of waste. The interest was in recovering the significant fee that they had paid to be able to set up shop on the path. The eco-development scheme treats the EDCs as stakeholders who are key players in protecting the fragile forest habitats that Lord Ayyappa resides in. Firstly they are drawn directly from villages surrounding the Periyar forests. This includes several groups of Adivasis who had lost ancestral land when the dam (1895) and later the Tiger Reserve (1978) were established. Secondly the EDCs do not pay any annual or seasonal rent for the privilege of setting up their shop. They are however, expected to be guardians of the forest and to use sustainable resources for energy. They help keep their path areas clean and use Forest Department supplied rubber trees for fuel rather than the natural forest biomass.

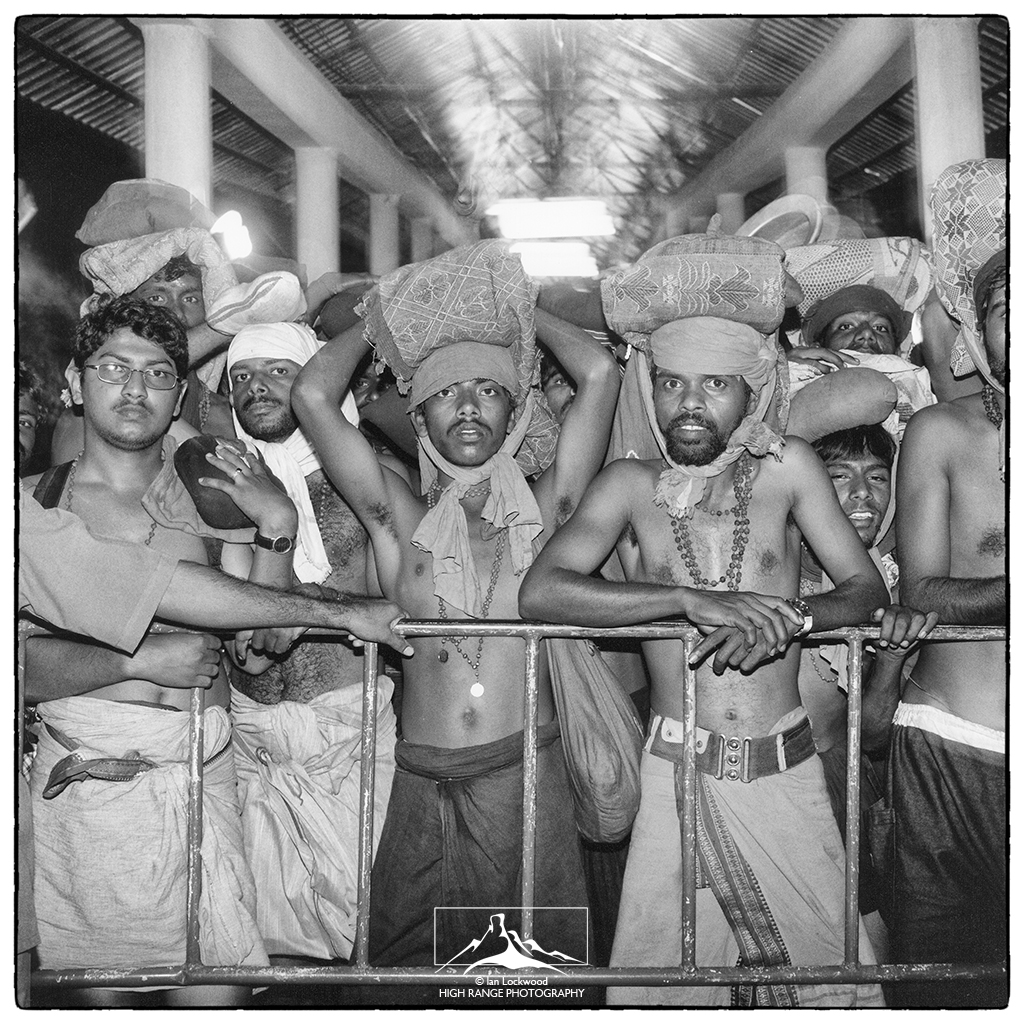

I stopped at several EDCs on my way down to the temple. Mainly I quenched my thirst with large glasses of buttermilk, but there were hot meals being served as well. At one stop I gazed at the steady stream of devotees as several noisy Malabar Grey Hornbills (Anthracoceros coronatus) cackled in the tree above the shop. The pilgrim groups were mainly composed of men, since menstruating women are not allowed into the temple. Many family groups had brought along young sisters and cousins and there were older women on the pilgrim path as well. As the path approached the temple the sounds of drums and chants drifted up through the forest. At certain point there were small breaks that allowed a glimpse of the temple with its gleaming gilded roof set amongst a concrete island of buildings and few lonely trees.

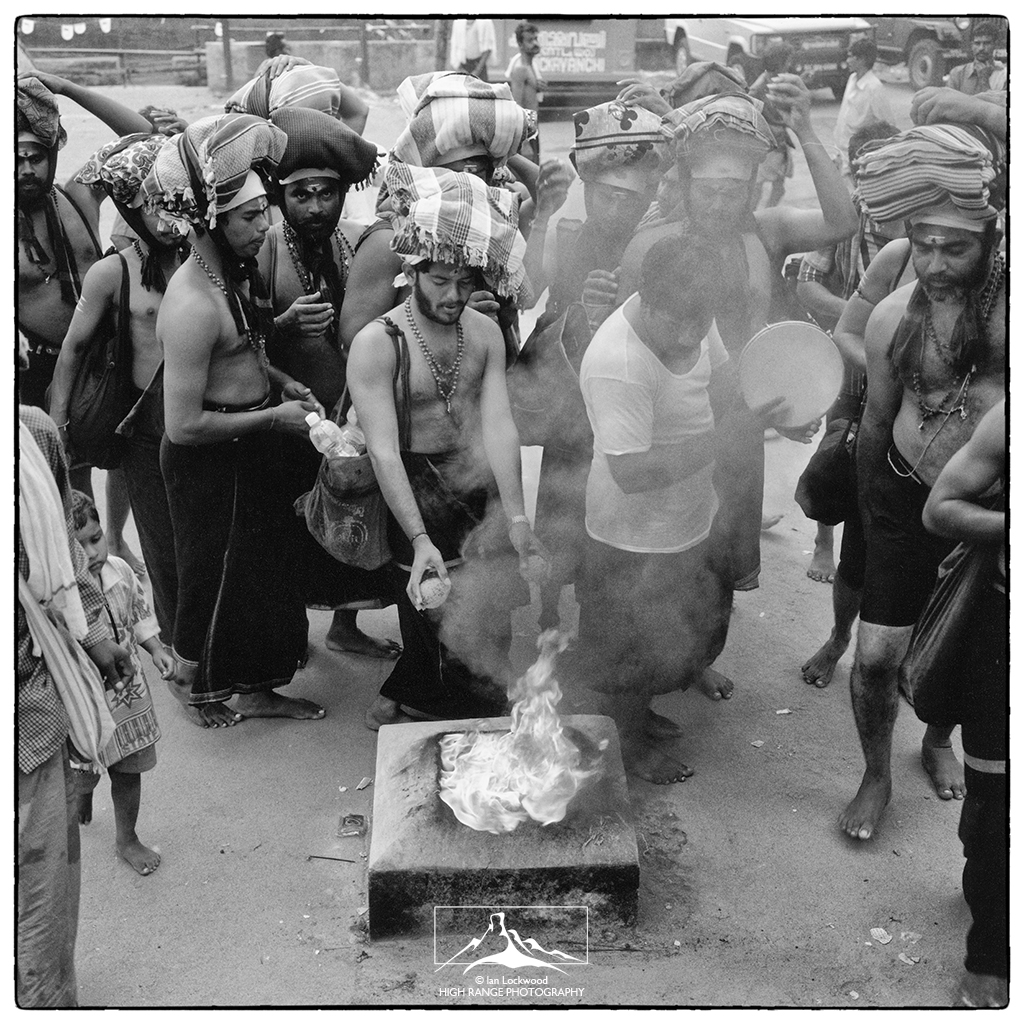

About a kilometer from the temple the forest abruptly gives way to a clearing on a hilltop that houses the Ayyappa temple. The temple complex is quite vast given that it sits amongst remnant rainforests. A few tall silk cotton trees (Bombax ceiba) stand sentinel over the arrays of shelters built for pilgrims on the outskirts of the temple. During pilgrimage season the magnified sounds of the temple and pilgrims drown out the calls of the forest. The scent of burning coconuts envelopes the area and it is hard to imagine that you are actually in a Tiger Reserve. I spent a night at Sabarimala and explored the different approaches to the temple. Photography is strictly prohibited in the temple premise and I focused my energies on the pathway. A steady stream of devotees wound its way up from Pamba and down from Uppupara to the central temple through the night. Their climax came as they waited in long ques and then climbed up the final 12 steps to the Swami Ayyappa Temple.

Pilgrim’s Path Away from Pamba

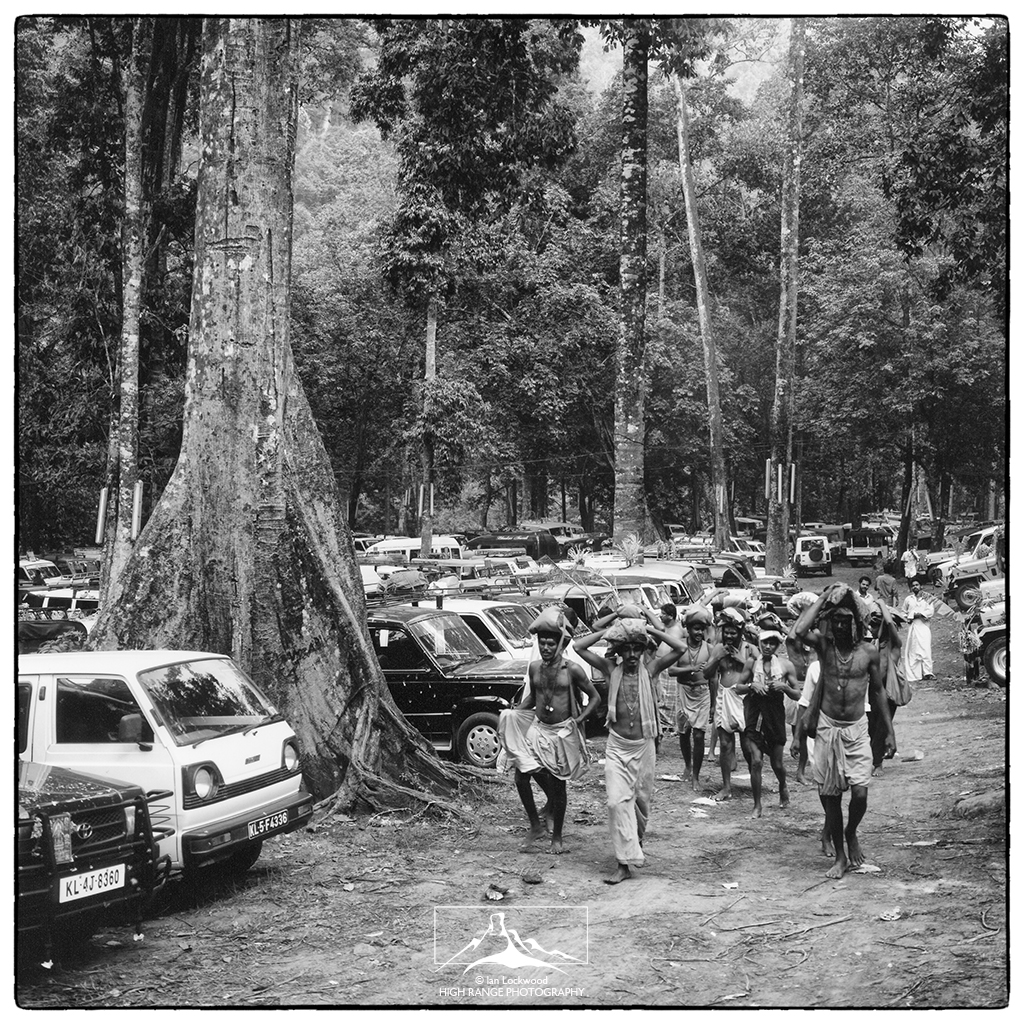

My pilgrimage led me away from the temple, to the base at Pamba and then through the lower forests to the entry point at Erumeli. The Pamba area illustrates some of the very serious challenges faced by such a large-scale pilgrimage in sensitive areas. Here parking lots of jeeps, buses and camped pilgrim groups crowd the spaces below large buttressed rainforest trees. Masses of people mill around during the season and an army of policemen are employed to help things run efficiently. The river suffers from severe contamination below the sacred bathing spot at the Pamba crossing. In the nearby forests the strain of such numbers on the fragile forest habitat are telling. Most of the large animals migrate out of the temple forest areas during the December to February season. Newspaper articles report plastic waste showing up in elephant feces. In recent years there have been calls to further improve road access to Sabarimala. There has even been a proposal to put in a rail line! The Forest Department is under pressure to denotify parts of the tiger reserve as well as the adjoining reserve forests to facilitate more pilgrims.

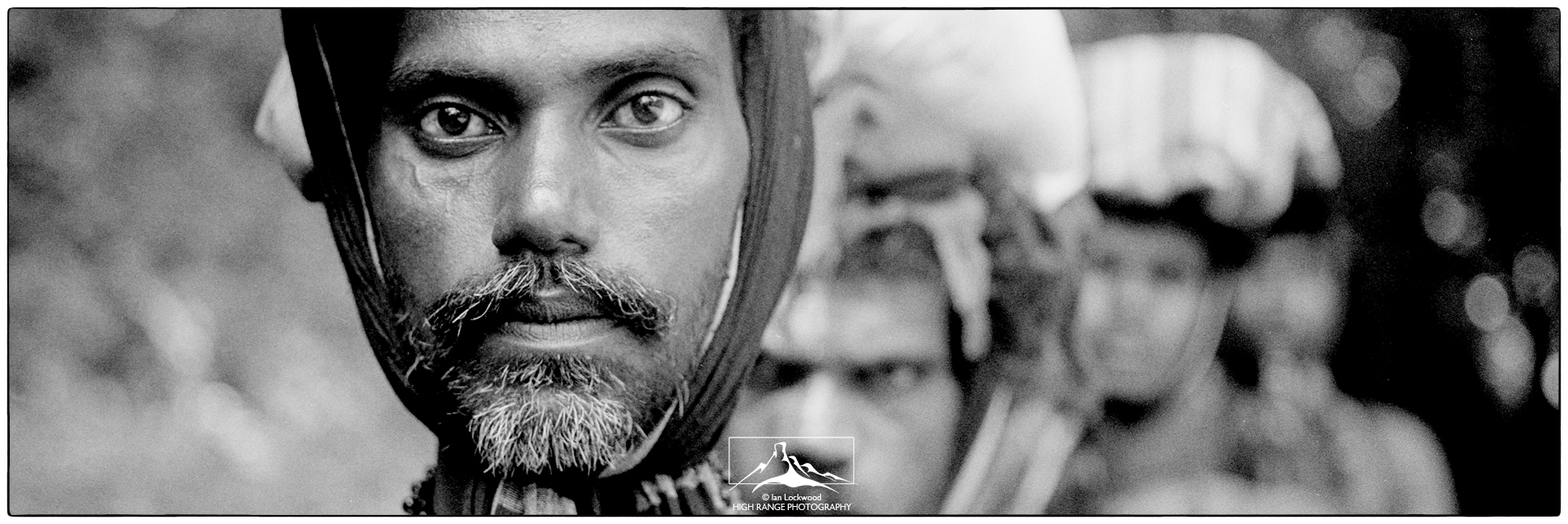

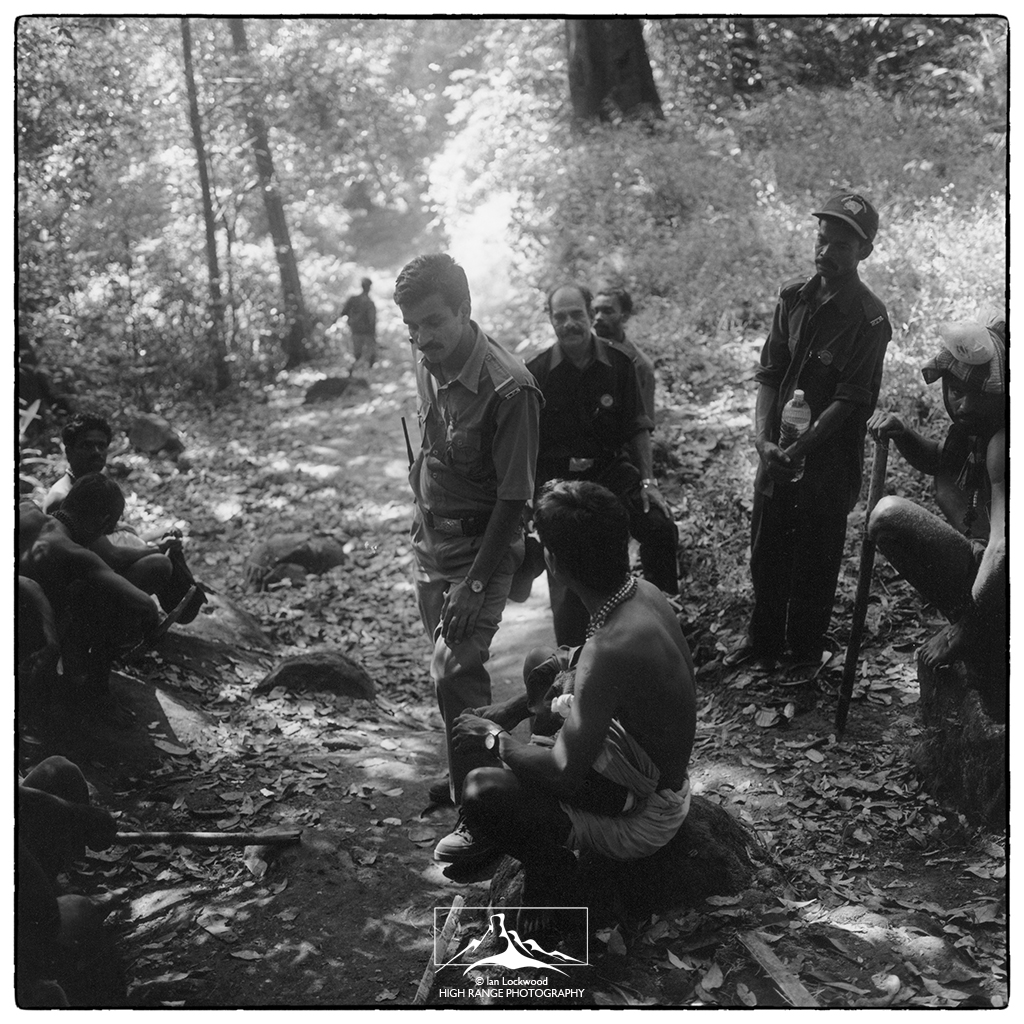

On the path leading out from the temple I followed the Pamba River to Erumeli with S. Sivadas, then the senior PTR officer in charge of managing the EDCs and other initiatives. Sivadas is not an ordinary forest officer. With a generous beard and contemplative look he could easily be mistaken for a sanyasi in kaki uniform. He speaks with his staff and the EDC members in an empathetic yet deliberate manner. He is as comfortable discussing Krishnamurthy’s take on nature as he is gleaning insight from Edward O. Wilson or other modern biodiversity apostles. He represents the high commitment, sincere interest and outright passion that is exhibited by a generation of officers in the Kerala Forest Department. I had first met him in a lonely bungalow on the edge of Eravikulam National park when he was the assistant wildlife warden there in the early 1990s. Now nearly 10 years later I am tagging along as he makes his rounds on foot in the sacred forests of Lord Ayyappa.

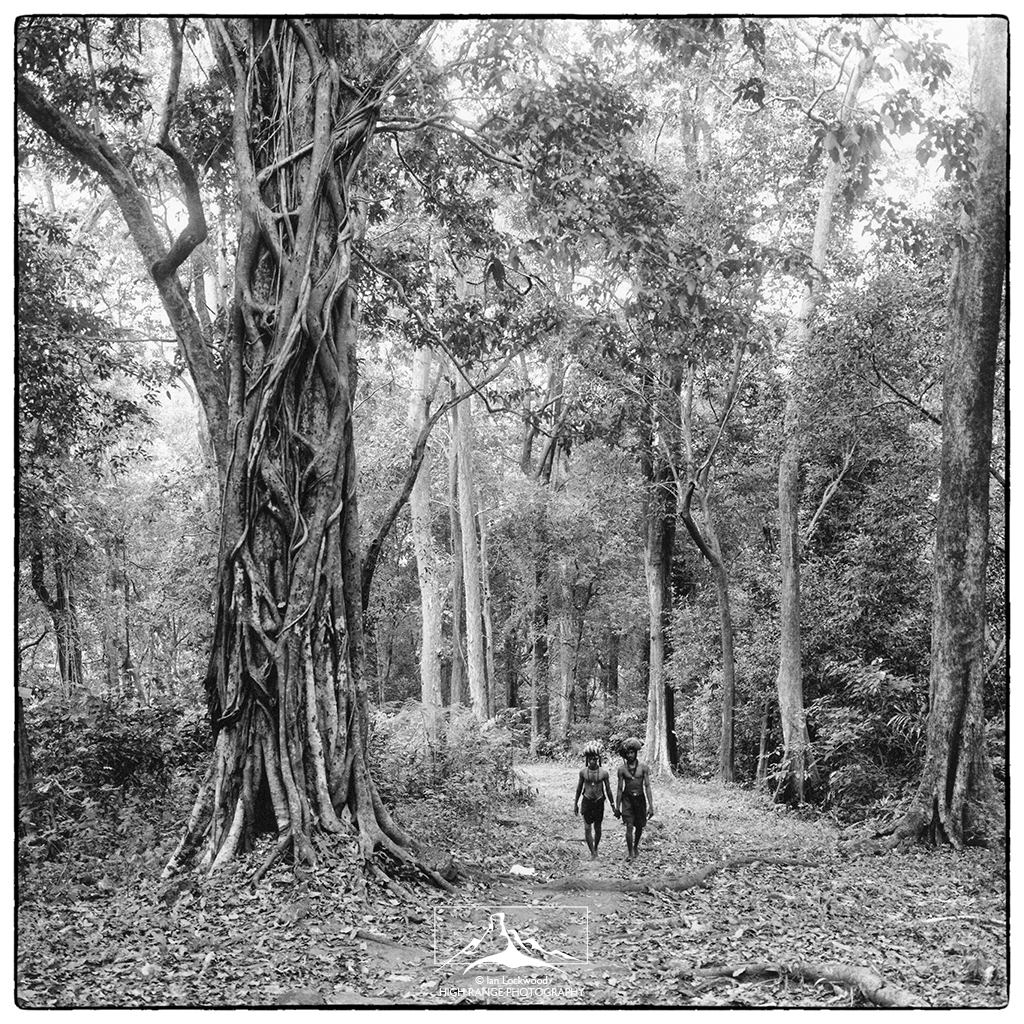

The 17-kilometer hike to Erumeli from Pamba leads through impressive tropical rainforest. Gigantic trees with canopies nearly 50 meters high tower over the river and path. There are signs of degradation on the edges of the pathway but this is the best-preserved forest that I’ve seen on the trek. A troop of Nilgiri langurs (Semnopithecus johnii) and a lone Malabar Giant Squirrel (Ratufa indica) are feeding on fruit and leaves high above us. I’m on the look out for Great Pied Hornbills (Buceros bicornis) and happy to encounter a feeding flock of birds with babblers, drongos, trogons, sunbirds and treepies. We moved quite fast since Sivadas wanted to survey as many EDCs as possible and see how they are progressing in their preparations for the flow of pilgrims on the climatic Makaravilakku puja. I followed in his footsteps, pausing only briefly to photograph pilgrims and trees. Between stops we discussed the challenges of balancing conservation with religious traditions and the large numbers of pilgrims. Despite the pressure on the forest department to release more land for the temple Sivadas remained cautiously optimistic that this tricky balance could be achieved through the use of community based conservation models such as the EDCs.

My pilgrimage came to an end at Erumeli, a curious settlement where Ayyappa devotees visit a Muslim shrine of Vavar Swamy on their way to Sabarimala! This fusion of religious ideas seemed to be emblematic of the very positive spirit of the Sabarimala pilgrimage. Balancing these ideals with the reality of such large numbers of 21st Century pilgrims in a Tiger Reserve is an enormous challenge. The Kerala Forest Department, with its innovative EDCs has shown that there is a way to provide for pilgrimage in a way that benefits pilgrims, local communities and the habitat. Surely, Swamy Ayyappa, astride his tiger, would be pleased with these initiatives to protect his abode.

This story and photo essay was based on several journeys to Sabarimala in 2001-02. The story was first published as “the Journey is the Destination” in Frontline (December 2006).