The man next to me, a young pilgrim with a fragile frame, is muttering a prayer, just barely discernable over the sounds of thunder and rain lashing down on us. A ferocious wind is blowing in from the north-east and threatens to blow us off the precipitous summit that we are bivouacked on. Flashes of lightening illuminate gnarled trees and the profiles of my companions huddled under a tarp. It leaks like a sieve, but we’re holding on to it with all hands, lest the wind blows away our only sense of security. Surely, the young pilgrim’s prayers are going out to Lord Agasthya, the great sage whose mountain we are camped out on. Agasthyamalai, at 1866 meters, is the highest point in the southernmost tip of India and one of the richest biodiversity zones in the entire Western Ghats. A stone’s throw to the west, the mountain drops for a perilous 700 meters-straight down into the tropical forests of Kerala. The drop on the other three sides is little better and none of us are happy about the idea of a sudden evacuation. Normally, visitors don’t stay overnight on this magnificent peak and, if the weather is anything to go by, the gods aren’t pleased with our choice of a camping spot.

On a map the collection of rugged mountains near the southern tip of India appear as a dark, insignificant blotch, just a shade different from the surrounding plains. It is certainly misleading, for the Ashambu Hills that lie south of the Shencottah Gap support one of the richest concentrations of biodiversity in the whole Western Ghats chain! Crowning these mountains at 1,866 meters is a distinctive peak that holds a special place in the range. Pothigai or Agasthyamalai (also spelt as Agasthyakoodam in Kerala) has long been revered as a sacred mountain associated with the sage Agasthya. In more recent years it has been recognized for its phenomenal diversity of life forms. For a mortal human being it is hard not to be swept away by Agasthyamalai’s towering profile and magical aura.

No Ordinary Mountain

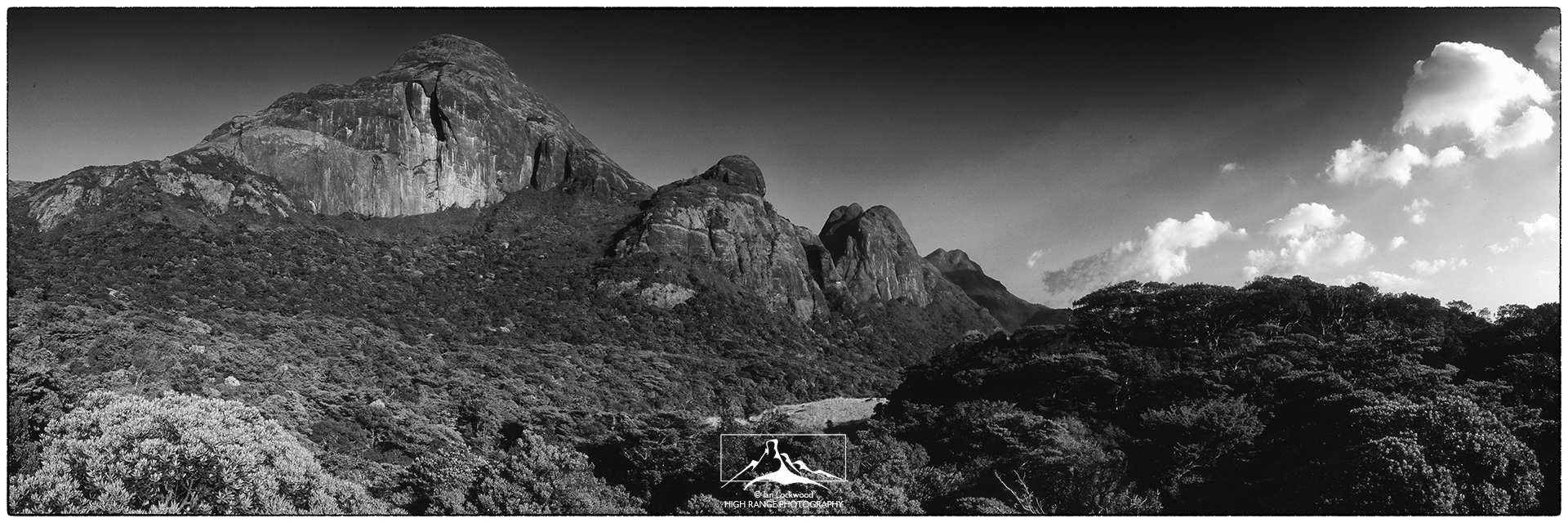

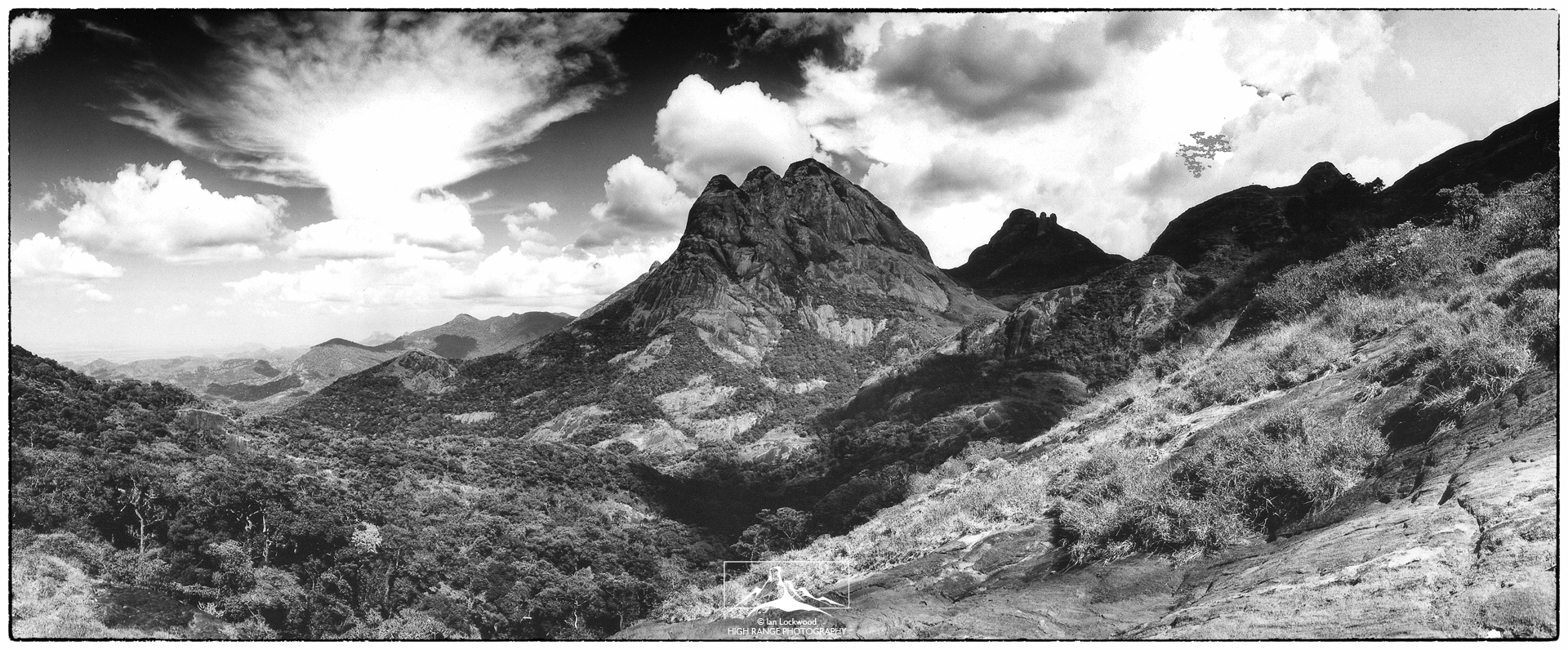

Agasthyamalai is no ordinary mountain. Amongst the steep slopes of scrub forest, valleys of dense tropical rain forest, and jagged peaks, Agasthyamalai stands sentinel. Agasthyamalai has a distinct conical profile that is nearly identical from both eastern and western sides. From either Trivandrum in the west or Tirunelveli in the east it stands out as a distinguished peak amongst a range of sharp, craggy mountains. Relatively speaking it is a lesser peak in the chain of mountains that make up the 1,400 km long Western Ghats. Dodabetta in the Nilgiris (2,623m), Karnataka’s Mullayanagiri (1,918m) and Anai-Mudi (2,694m), South India’s highest peak are all far higher. Yet, there is something about Agasthyamalai that transcends mere height and size really doesn’t matter in this equation. Agasthyamalai’s profile bears an uncanny resemblance to Tibet’s Mt. Kailash and this has perhaps lead to its aura and many myths.

Similar to Sri Lanka’s Sri Pada or Adam’s Peak (2,243 m), Agasthyamalai towers above its neighbors in a dramatic fashion and has an unmistakable spiritual quality to it. Both of these mountains share geological origins, floristic wealth and are appreciated for their spiritual significance. Agasthyamalai’s namesake is derived from the great sage who is said to have given the Tamil language to India’s Dravidian people many years ago. Agasthya is associated with herbal remedies and is often depicted holding a stone crusher in one hand and a vessel in the other. The significance of this and the fact that Agasthyamalai hills are known for their medicinal plants should not be overlooked. The most pertinent myth regarding the mountain relates to Agasthya and the marriage of Lord Ishwara (Siva) and Parvathi in the heavenly realm of Mt. Kailash (the sacred peak in Tibet at 6,740 m). When the wedding was announced all the world’s gods, rishis, and people migrated north to the Himalaya. As a result, the earth went off balance and became dangerously wobbly. With disaster looming, Ishwara asked Agasthya to go south and balance the situation through meditation. After meditating and praying on the mountain that now bears his namesake the world was once again put in balance.

DAY I

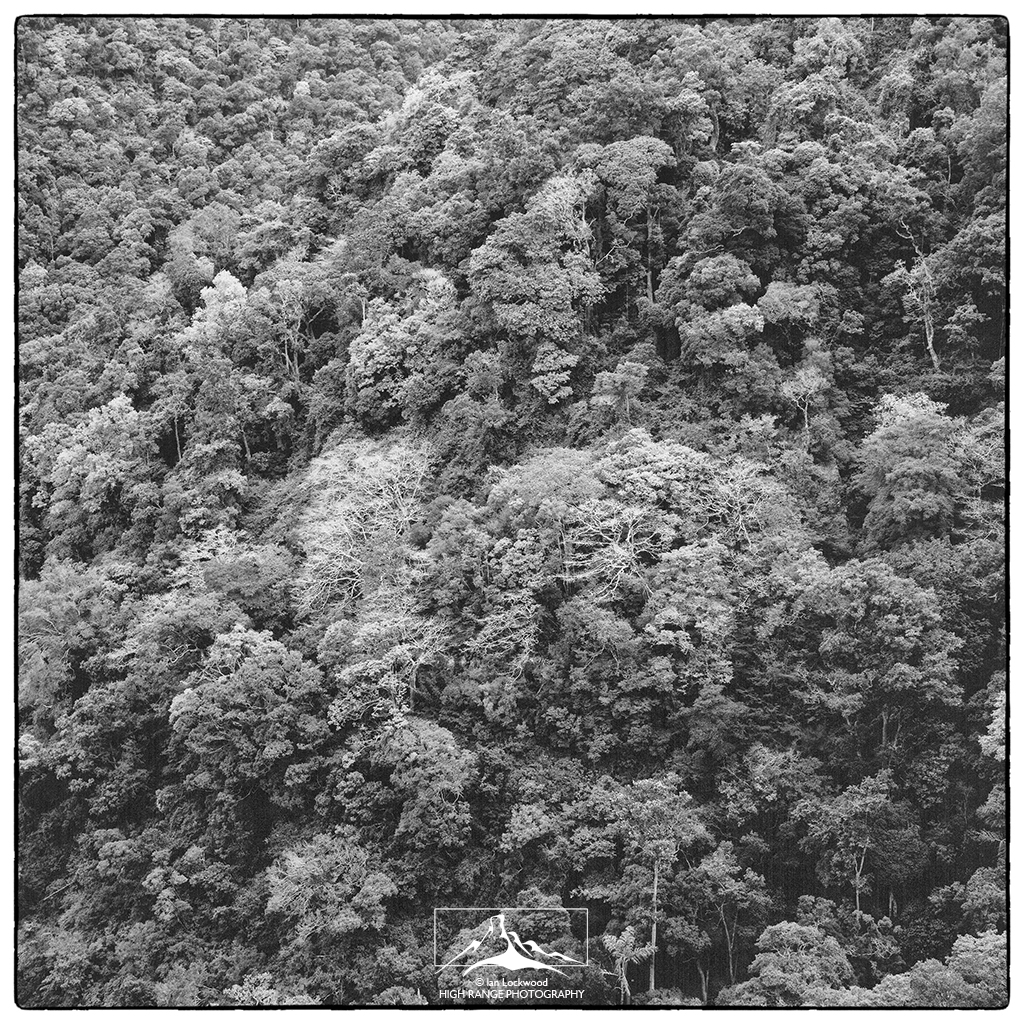

It is mid-morning and our team is motoring across Karaiyar reservoir to the starting point of our four-day expedition to Agasthyamalai. Built in the 1960s as part of a massive hydroelectric scheme, the reservoir is surrounded by steep hills carpeted in dense evergreen forest. Protruding from these hills is a jagged ridge of granite peaks that includes the pyramid shaped Agasthyamalai. My team is made up of five friends from the Dhonavur Fellowship, a community with strong conservation ties in these hills. Jerry Rajamanain, their leader, has a special interest in Pothigai (the local name of Agasthyamalai) and has been instrumental in organizing this expedition. We are supported by several Kani men who will guide us to the summit and help carry food.

Our boat approaches the sandy shore littered with leaf debris and huge blackened tree stumps. A wide waterfall cascades over house-sized boulders before emptying into the dark waters of the reservoir. This is the sacred Tambraparani River, one of the most important rivers whose watershed is made up of the forested slopes of Agasthyamalai. We clamber up ancient rock-cut steps on the side of the falls. It is slippery, steep and would dissuade casual explorations beyond the falls. Soon we have the whole Tambraparani River to ourselves. Two fairy bluebirds and a group of ruby-throated black-crested bulbuls flitter in a low tree by the stream. Pausing we can just see the summit of Agasthyamalai peaking over the canopy of trees. It is an awing sight and we are excited to be back. Just a few months ago, my Dhonavur friends and I took an unsuccessful trip to Agasthyamalai. The lingering North-East monsoon had prevented us from reaching the summit and now, seeing it free of clouds, brings on a wave of excitement.

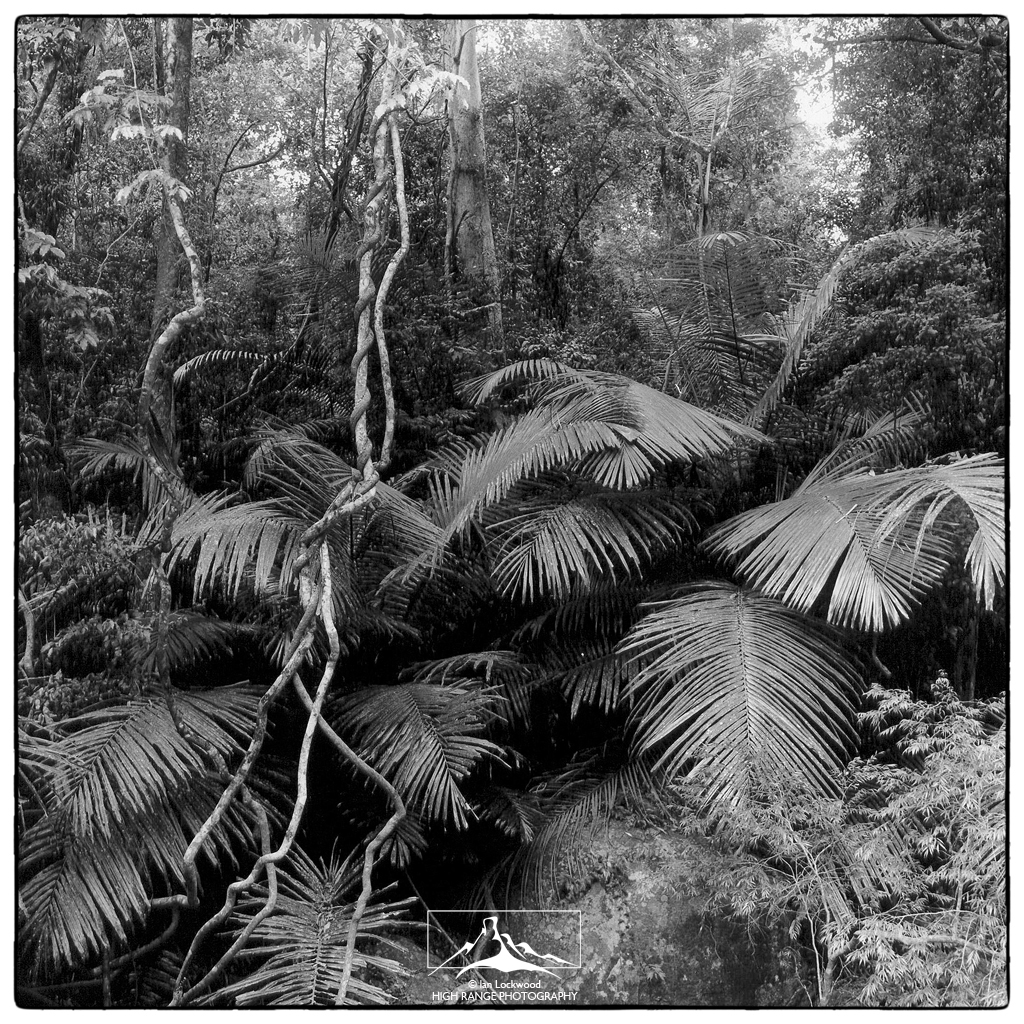

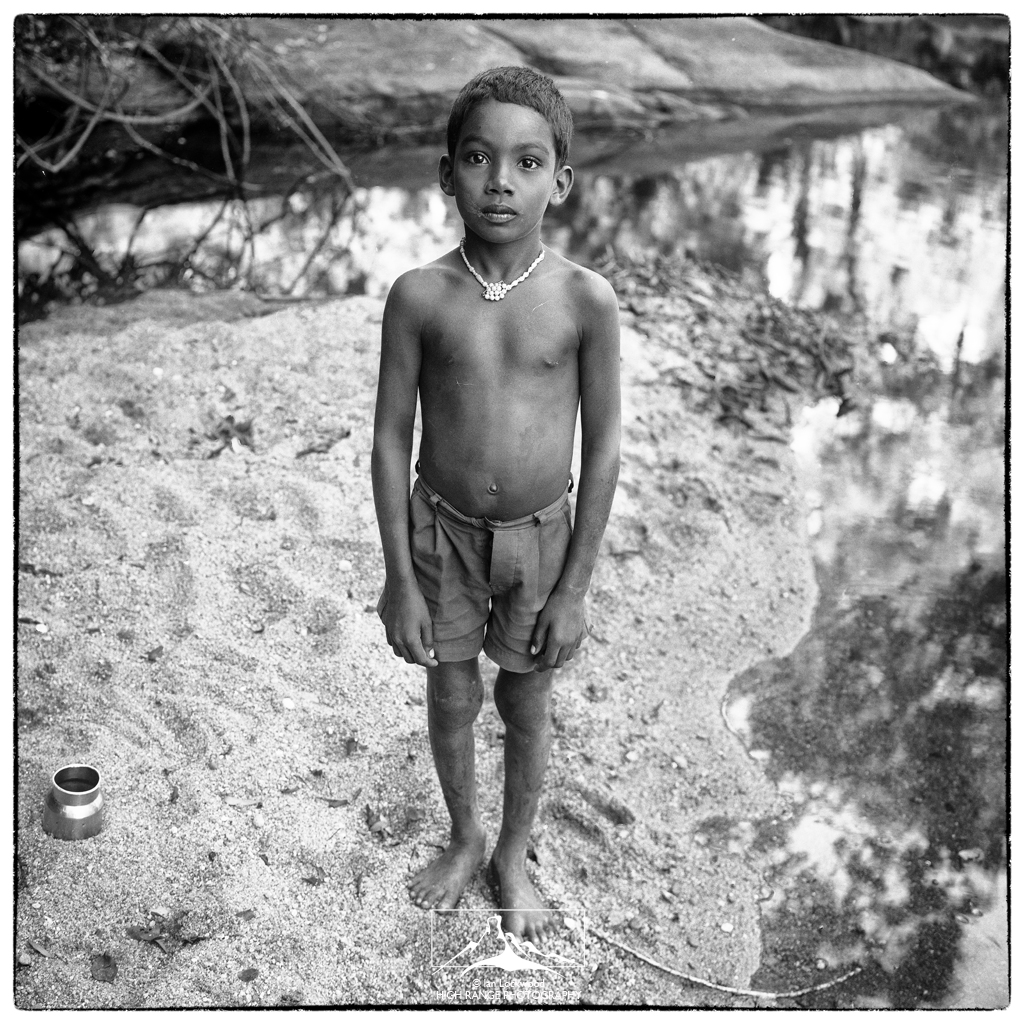

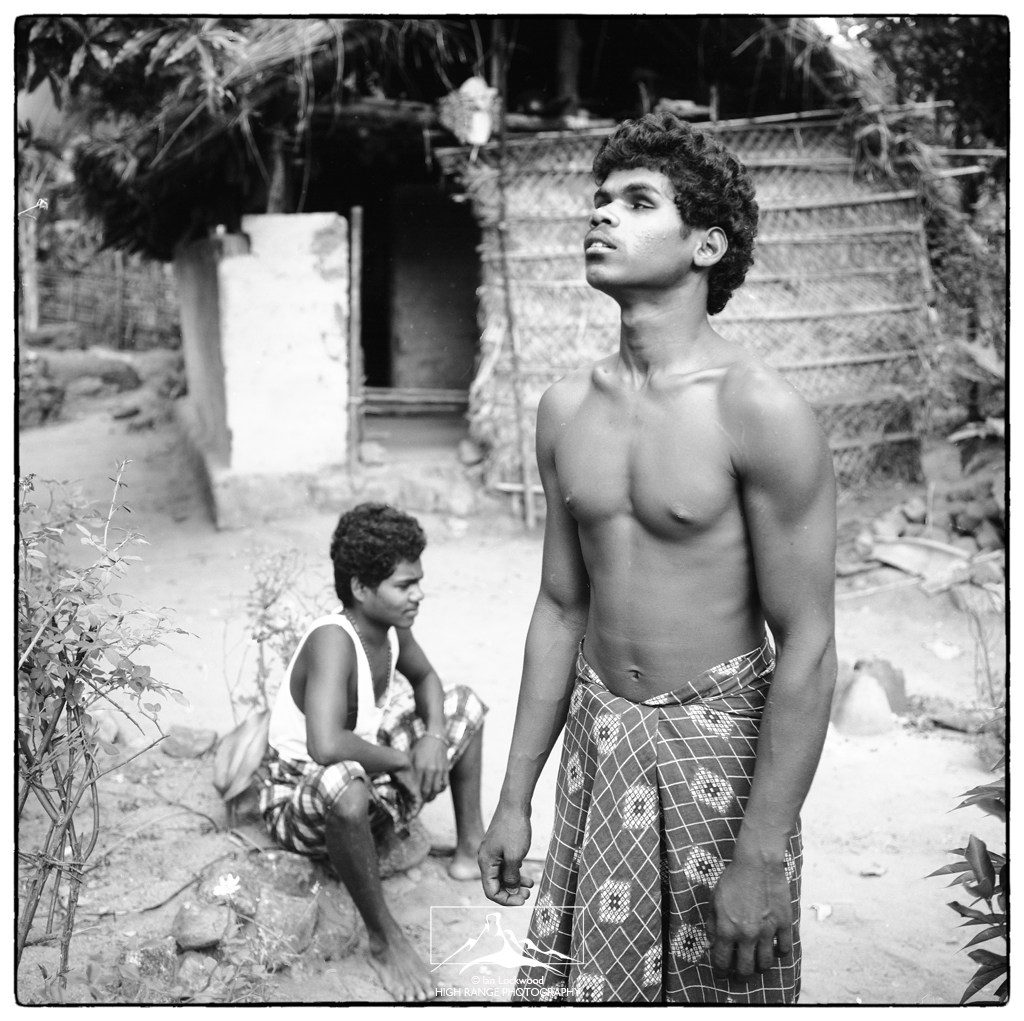

Manikandi, the most knowledgeable of the Kani men, leads us along the river and then cuts up into the forest on a small path. From the scorching heat of the open we enter the shaded, cool world of the rainforest. Gigantic canes and towering lianas crowd between large buttressed trees. Cicadas fill the air with their deafening calls. Our destination today is the Kani tribal settlement of Injukuli. The Kanis, the indigenous forest dwellers of the Agasthyamalai hills, once practiced shifting cultivation, but many have been relocated out of the protected areas in the interiors of KMTR. In the 1990s much attention was focused on the Kanis when they struck up an innovative deal to share the proceeds of developing the Arogyapacha (Trichopus zeylanicus) plant with a pharmaceutical company. This plant grows wild on the Kerala side of the Agasthyamalai hills and is known for its invigorating properties that reduce fatigue. However, what promised to be a landmark deal to benefit indigenous forest dwellers got bogged down in government red tape and the project floundered.

Injukuli consists of a dozen scattered thatched huts and cleared fields, set under the imposing Agasthymalai. We set up camp near a house owned by a friendly Kani family. Their three children, lead us down to the Tambraparani and show us the best spots for an afternoon swim. We turn in early, knowing that tomorrow promises to be a difficult day of trekking. Above us, suspended in a cloudless sky, the moon is almost.

DAY II

The sun rises early over Injukuli casting a crimson glow over the towering trees and cliffs that enclose the settlement. Two groups of pilgrims have also spent the night and are making their way to the summit. Their presence surprises me, since the permissions to visit Agasthyamalai were difficult to come by. None of us expected that our group would have company on this side of the mountain. Most pilgrims climb Agasthyamalai using the severely worn path through Pepara WLS on the Kerala side. During a two-month season, 50 pilgrims are allowed in a day through this route. It is an arduous trek but one that offers a chance to conduct a puja at the small Agasthya shrine at the summit. However, the stress of even such modest numbers is telling. On our first summit bid we had walked out via Pepara and had observed signs of garbage, fire and degraded forest. This might be expected in a holiday resort, but on the slopes of a mountain known for its sensitive plant diversity and endemism? In discussions with my friends in the Kerala Forest Department, it was clear that the impact of this remains a concern, but one that is tempered by the fact that it is a religious pilgrimage and nearly impossible to stop.

By 7:30 we start out on a disused path that winds its way from Injukuli up the Tambraparani and over several valleys to the base of the massive Agasthyamalai. The first bit of the trail takes us through dense evergreen forest with an exquisite understory and towering trees. The Cullenia excelsa tree, much favored by Lion Tailed Macaques, is abundant. Most pleasing to me are the dry conditions and dearth of leaches. A white bellied treepie, is calling noisily in the canopy just above us. Several hours later we reach, Pongalam, a stream-fed pool that offers the last source of water on the way up to the summit. It is surrounded by dense Ochlandra reed brakes that are a favorite haunt of elephants. We rehydrate on a homemade concoction of ORS, feast on tamarind rice and rest before starting up the side of Agasthyamalai.

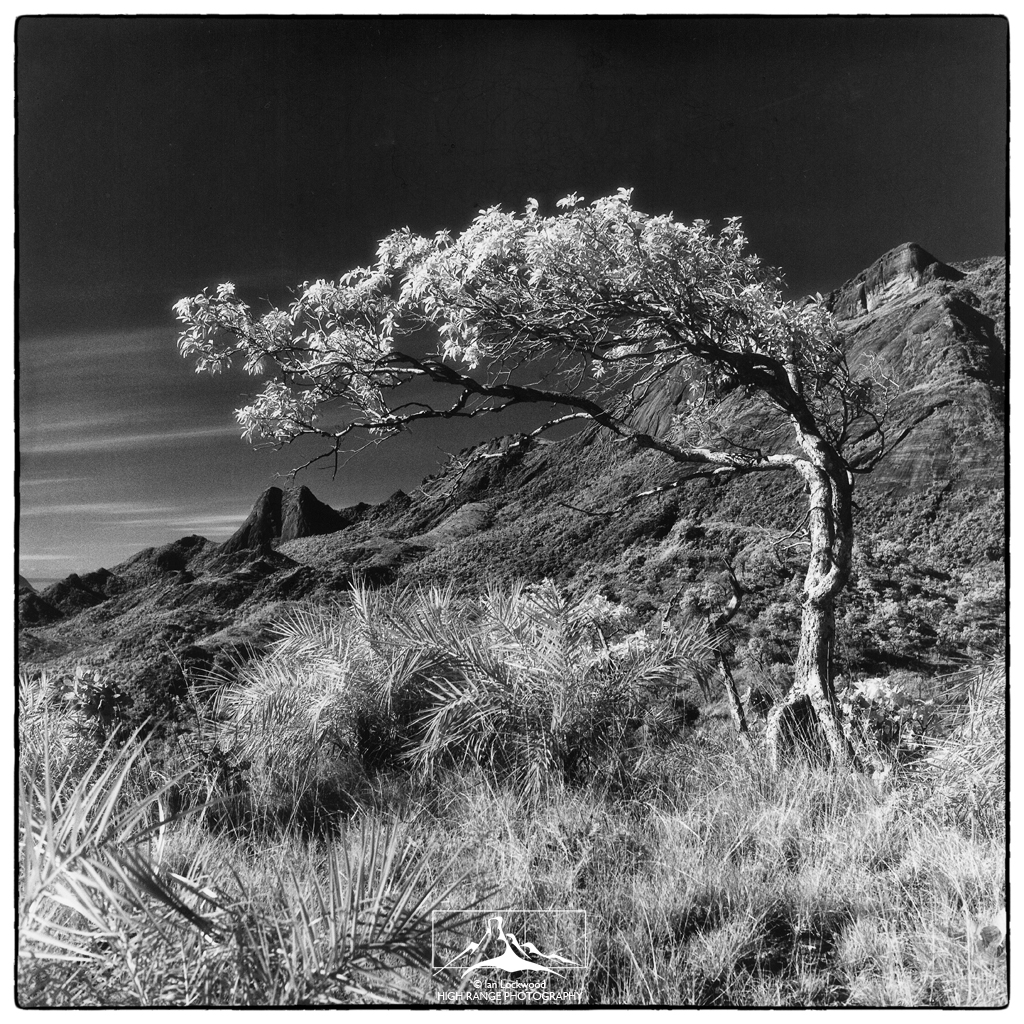

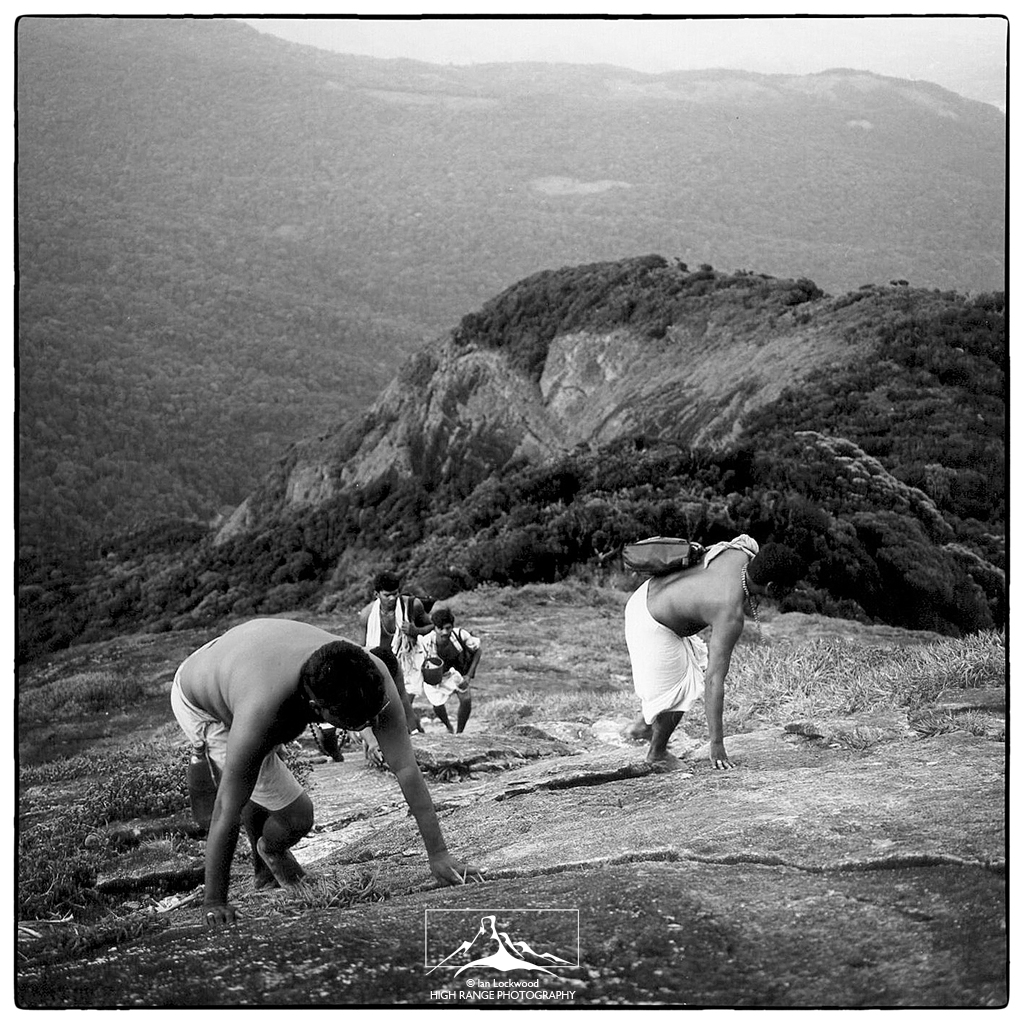

After Pongalam the path ascends at a dizzying angle up the exposed sheet rock that forms the near vertical eastern ramparts of Agasthyamalai. At times our path ascends at gradients that force us to use all fours. Clearly this would be impossible during the rainy season. The path passes through clumps of the stunted tropical evergreen forest that are distinctive to the slopes of Agasthyamalai and the neighboring peaks. Severe wind keeps the canopy low and ancient trees are deceptively short and stunted. Although it looks and feels like shola forest it is technically not, since this forest is below 1900 meters (the lower limit of shola forests). We see the endemic Bentickia condapanna palm trees clinging to precarious slopes. They appear strangely out of place here, as if Dr. Seuse had painted them on to the mountainside A group of brown-backed needletails and other lesser swifts are darting in huge circles over our heads. I look in vain in the grassy clumps for the enigmatic Paphiopedilum drury orchid. This ladyslipper orchid is restricted to the slopes of Agasthyamalai and is, perhaps, the rarest epiphyte in the entire Western Ghats chain. Just as I’m dreaming about stumbling across a paph, I spot several large clumps of bright pink Aerides Ringens and am content taking pictures of them.

After walking under an enormous wall of charcoal-black sheet rock, we find ourselves approaching the main north-south ridge of the mountain. Now in thick forest, we join the more worn trail from Pepara. It is late afternoon and I am perspiring heavily. I get ahead of the group and emerge on the exposed shoulder of Agasthyamalai. The view around me is spectacular. I can see from the Mundanthurai Valley clear around the mountain to the western side. To the south the lesser peaks protrude from the forest in a dazzling array of weathered granite and windswept vegetation. Surprisingly there is practically no wind- a significant change from the January trip when we had nearly been swept off the lower slopes every time we stood up! In the distance there are big thunderstorms but the peak is enjoying what seems like a rare calm.

The final approach to the summit is straightforward, although there are a few unnerving rock faces to get up. I pass a group of pilgrims at a particularly difficult spot. A few more steep bits and then a final patch of forest. Finally I am there, standing on top of Agasthyamalai, breathing fast and elated by the panorama spread before me. The summit is dome-shaped with a pile of rocks at the high point. Visitors have vandalized it by painting their names on the rock in an ugly shade of yellow. On the southern side of the summit, a small crown of forest protects the modest Agasthya deity. He is a short, stout god with a healthy stomach and long beard, protected only by a circular shade.

By the time we set up camp it is twilight and the best spot, protected by a ring of trees, has been taken. We find a sloped patch of grass nearby and are able to tie up our large tarp. Meanwhile two or three different thunderstorms are lashing the eastern plains and the ranges south of Agasthyamalai. It seems obvious that we were going to have precipitation sometime soon. Knowing that we are on the highest peak in the area, I can’t help but being slightly nervous about what awaits us.

We enjoy a subdued sunset and a murky moonrise behind layers of thick clouds. When it emerges later the moon casts an ethereal glow over the hills and approaching thunderheads. The storm moves closer and we take refuge under the tarp, eat a dinner of biscuits and prepare for the inevitable. It hits around 8:30, starting with ferocious winds that threaten to blow our cover off the mountain. At the first gust the ten of us under the tarp grab on to corners and folds. For the next two hours we cling to our scanty cover. Lightening bolts strike all around us and light up silhouettes of the wind-blown trees. Thunder rolls through the valleys around Agasthyamalai. Things are more or less fine, except for the major fact that the tarp leaks horribly! Sitting up in my sleeping bag I put on my rain jacket and contemplate taking out my umbrella. However, there is no room for this luxury and I’m soon drenched. The second group of pilgrims, all six of them, takes cover with us and it is a cozy gathering, to say the least! They seem a little surprised by nature’s furry and suggest that Agasthya is upset about us sleeping on the summit.

The storm does eventually clear and by midnight we are left with the sounds of water dripping through the tarp and frogs croaking in the grass. My sleep is erratic at best. I wake every hour or so, excited by the prospects of dawn and a new day. I know that the rain should wash the plains and mountains clear and I am eager to see and photograph it all!

DAY III

I get up and out of the slushy sleeping bag at 4:30 am. A poncho has protected my cameras and I move them out to the summit area. A light breeze is blowing and there is still a magical otherworldly glow from the setting moon. The lights from towns on the eastern plains twinkle brilliantly and the brighter constellations are visible. I want to see the view in the complete darkness and witness dawn from the very first light. Jerry, the only other team member interested in giving up sleep for the first views, joins me. We locate both Tirnulveli in the east and Trivandrum in the west, identified by their large clusters of twinkling lights. Four different lighthouses are visible, demarcating the Arabian Sea in the west and Gulf of Mannar in the east.

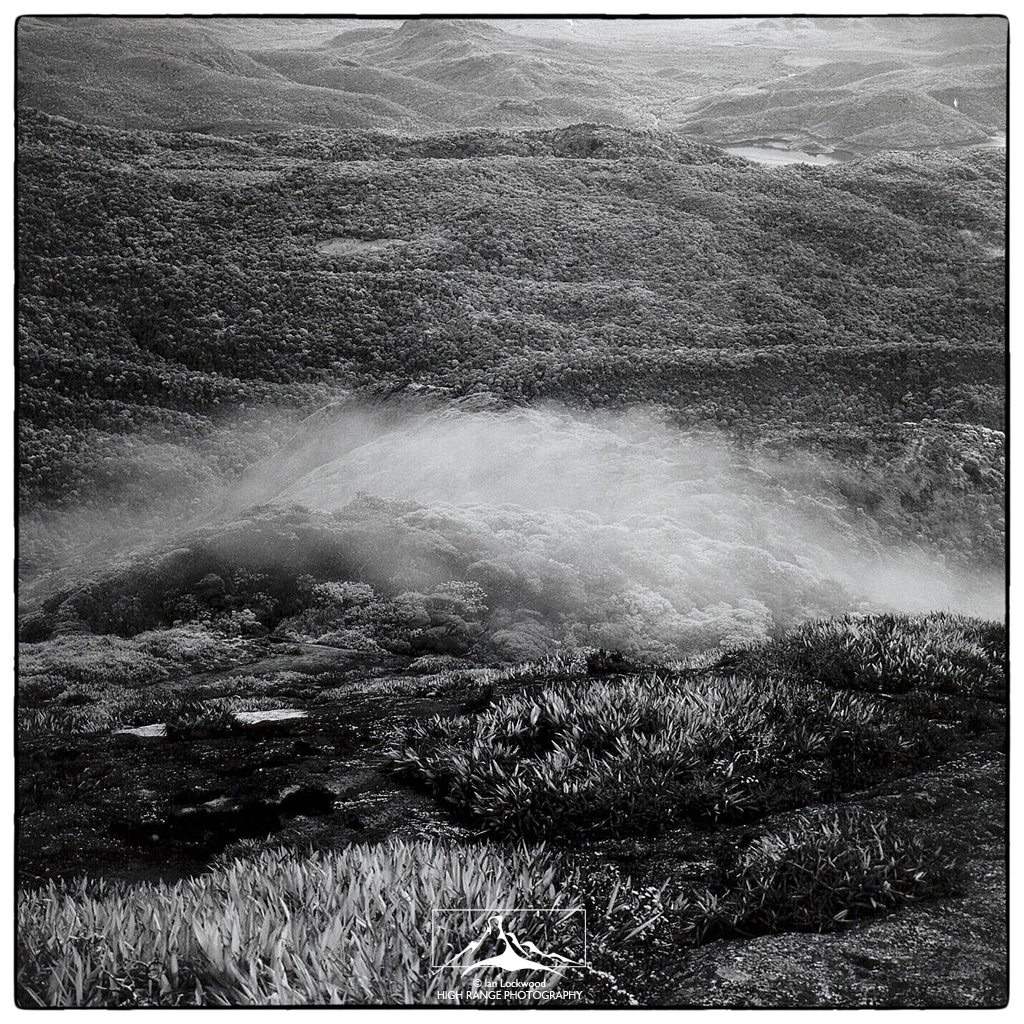

Dawn is a magnificent affair on Agasthyamalai’s summit and makes the stormy night worth all its fear and discomfort. As the rays of the new day fill the sky they paint cirrus clouds in fantastic hues of gold and scarlet. A kestrel is hovering over the precipice near the summit and grey breasted laughing thrushes are chattering in the trees by the Agasthya shrine. Thanks to the night’s showers the plains and hills are indeed terrifically clear. Looking north we are blessed with a terrific view of the dark evergreen forests of the Mundanthurai range. The azure mountains ranges stretching beyond the Shencottah Gap and up towards Periyar Tiger Reserve are striking.

Then something incredible happens. The sun, just a hair above the horizon, projects the conical shadow of Agasthyamalai into the light haze of the west. It creates a surreal pyramid-shaped shadow that shifts as I walk along the summit. This is a phenomenon often observed by mountaineers on high peaks at sunrise. It is well recorded on Sri Lanka’s Adam’s Peak, but this is the first time I’ve seen it happening in the Western Ghats in such an extraordinary fashion. The magical shadow doesn’t last longer than ten minutes and soon disappears when the sun slips behind a low cloud.

The pilgrims head down almost immediately, while we linger to dry things out and enjoy the view. Jerry and I work on identifying the local peaks. As the sun rises higher we are thrilled to spot both coastlines! They are not as clear as I had imagined, but the dark blues of the seas are distinctly visible.

By mid morning wispy mist is gathering at Agasthyamalai’s summit and we make a move down the mountainside. The night’s rain has made the rock faces slippery and we proceed with great caution. I flush a Peregrine falcon from a patch of grass. It goes flying out over the edge and gives its mournful alarm call. Although our knees start to feel like jelly the decent takes much less effort than yesterday’s climb. At Pongalam I use the opportunity to bathe in the pool and am soon convinced about the divine properties of the ritual. The hike back to Injukuli is long, but less tiring and we are back by late afternoon.

DAY IV

Our final day in the shadow of Agasthyamalai goes smoothly. We pack up and say thank you to the Kannis. It is a gentle path back to Banerthetum and I walk most of it alone. I am able to spot a troop of Nilgiri langurs and two Malabar giant squirrels but am disappointed about not seeing any Liontailed macaques, the denizens of these forests. We’ve seen plenty of spore on the path-sloth bear, civits and large cats, but I am surprised by the few sightings of animals and birds. On past trips to KMTR I have had excellent sightings of great pied hornbills, Malabar trogons and other avian species, but this time the bird sightings have been modest. Just before descending to the falls and catching the boat out we take a refreshing bath in the Tambaraparani. It is Sunday and the falls are packed with local tourists taking baths and picnicking. We must look a little strange, emerging from the side of the waterfalls, unshaven and thinner, but elated after an unforgettable pilgrimage to Agasthyamalai’s summit.

Originally published as “Heritage Hills” by Frontline in May 2005. Text & Images: Ian Lockwood

REFERENCES

Anurada, R.V. Sharing With the Kanis: A Case Study from Kerala, India. ND. Pune, Kalpavriksh. Print & Web.

ATREE. “Special Focus on Religious Enclaves.” Agastyar Newsletter. Volume 5 Issue 3, 2011. Print & Web.

Johnsingh, A.J.T. “The Kalakad–Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve: A global heritage of biological diversity.”Current Science. (Vol. 80. No. 3) 2001. Print & Web.

Lockwood, Ian. “Agasthyamalai, A Mountain of Significance.” Ian Lockwood Blog. December 2011. Web.

Nair, Ashish Chandra. The Southern Western Ghats: A Biodiversity Conservation Plan. New Delhi: INTACH, 1991. Print.

[wpgmza id=”1″]